I write, or rather add, this post to share an argument that I wanted to make for a decade and finally did at the international conference “Entangled Englishes in Translocal Spaces,” organized by University of Liberal Arts Bangladesh, Center for Language Studies and the Department of English and Humanities in October 2021.

In the presentation, I covered:

1) how do we counter the global hegemony of English? and, (for the purpose of)

2) how do we make knowledge valuable for society?

Here is a video of it on YouTube.

And below is the text form—

I will first highlight how the hegemony of English is essentially 3 fingers pointing at ourselves, our identities and privileges, our self-serving interests and investments in English (which we’ve gone on to pluralize in discourse and practice) — with our index finger pointing at the Englishes and the thumb, sideways, at the geopolitics undergirding the dynamic.

That is, I argue that our scholarship and our teaching must be valued not just in terms of what we preach but based on what we practice — vis-a-vis our contribution to the communities around us that don’t have the same privileges that we do, communities to which we owe honesty as well as access to the knowledge we create.

As I will illustrate with the experiences of working with various groups of scholars across South Asia in recent years, we can counter the hegemony of Englishes by rejecting current premises and building new frameworks within which we can do research and publication and teach and advance new knowledge by making them all relevant locally, first.

Then I will share some more experiences to show that in order to do what I propose, we must disentangle English as a medium from English that we practically treat as the very goal of education and scholarship — in spite of all our pontificating otherwise.

I will do this within a translanguaging framework that allows us to disentangle from the power and privileges — instead investing honest efforts to mobilize all languages for what I call Scholarship 2.0 — a framework that could help us shift our approach toward a more grounded, more just, more meaningful scholarship.

Scholarship’s (and scholars’) goals must be to advance and use knowledge for social good, to affect justice, to improve the human condition — indeed, to save the planet — and we don’t have to do all these in English only.

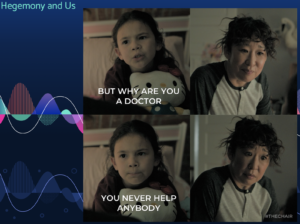

To begin with a bit of levity, here’s a somewhat silly but thought-provoking meme that a colleague shared on Facebook last week as I was working on the slides.

To begin with a bit of levity, here’s a somewhat silly but thought-provoking meme that a colleague shared on Facebook last week as I was working on the slides.

As you can see, a child asks her scholar parent, I think: “But why are you a doctor?”

Before our PhD has too much time to explain all the amazing difference we make in the world, the child says: “You never help anybody”!

What’s the point of being a doctor who doesn’t serve the sick? Or somehow support the needy.

The rhetorical fulcrum here is not the child’s ignorance about what PhDs do in the world but the innocent commentary on the apathy that too many of us show about the world of people, problems, needs, challenges … crises — right around us.

I want us to keep this child’s question in mind: Why do we do all the teaching and researching and critiquing of language? Specifically, about English, and Englishes, and some more about its hegemony? Or, any scholarship for that matter? Why? Who do we do it for? To what effect? For what social value? Toward what social-justice outcomes?

Uncomfortable as these questions sound, how many of us rhetorically (rather than ideologically) determine which language and what combinations we should use for which audience in what context and for what purpose and effect?

Frankly, I think we just love to encash the critique of English and we do little or nothing about the problems we discuss because the latter is not in our business interest. Some of us blame the West while serving its dominant status, inadvertently or not.

It’s not like the West, however we define it, rewards us for the service; we just happen to benefit from doing so. We localize and replicate and adapt and find value in cultivating the hegemony–with local spices and flavor.

Then we argue a little more how empowering the whole process of adapting and appropriating the power of English can be–for some of us, that is, though we seldom admit it.

We then go on to cherry-pick empirical evidence to justify what we want to–forgetting that our arguments don’t apply to the vast majority of members of our societies.

Most of us are complicit and complacent because we cannot break away from our personal privileges and pleasures offered by the status quo. Through our institutions and policies and frameworks of professional development and rewards, we have adopted competition, persuasion, conversion, and the regime of exclusion–all of which are mediated and maintained by English and its attendant political capital that we invest in and harvest of. We produce scholarship that is mostly inaccessible and therefore largely useless to our local societies–even the scholarship critiquing English.

কেন আমরা একে অপরের সাথে ইংরেজিতে কথা বলি?

Why do we speak in English with each other?

আমাদের প্রতিবেশীদের জন্য আমাদের প্রকাশনা কোথায়?

Where are our publications for our neighbors?

As you can see from the skewed maps of global “knowledge production” (meaning mainly journal publication), the imbalance is correlated to the non-use of our own languages–I borrow this map from an 2014 article by a South Africa-based colleague Laura Czerniewicz.

As you can see from the skewed maps of global “knowledge production” (meaning mainly journal publication), the imbalance is correlated to the non-use of our own languages–I borrow this map from an 2014 article by a South Africa-based colleague Laura Czerniewicz.

In the name of using a more widely shared language, we’ve only connected the cities, the elites, the privileged–or, people like us–who are, what, 2 or 4 percentage of our respective countries’ populations?

Across the world, increasingly, if any research and publication is done in English, it enjoys greater recognition and reward. From institutional practices to government policies to public understanding and aspiration to the very consciousness of scholars across the disciplines, strangely including us, the medium (English) measures the value of research–instead of its purpose in and contribution to society. It commands respect.

The hegemony of English–which points three fingers at us–is all-pervading and rapidly expanding — thanks to us.

और हम इसकी शिकायत अंग्रेजी में करते रहते हैं।

So, to get to the first part–countering hegemony–let me use one of the many experiences of working collaboratively–in this case creating a support network for two dozen scholars from across Bangladesh, India, and Nepal and from across the disciplines–and helping members of this community publish from research projects that had a social-impact foundation and goal. This 2019 group was supported by a local network of peers and mentors. The participants worked on projects such as an investigation of potato yield in Kathmandu valley, environmental content in ELT in Bangladesh, quality of bricks in Nepal, human-wild animal clashes in the South Asian countryside, and partition-induced violence in India-Bangladesh border.

After the project’s completion, using surveys and interviews, colleague Nasrin Pervin from Bangladesh, Pratusha Bhowmik from India, Surendra Subedi from Nepal, and me in the US wrote an article that is now under review. We report how scholars pursuing research with broader social responsibility in mind–rather than just for talking to each other–find far greater motivation to do research and publication. Our article shares the findings of the action-research component of the community support, showing that when there is community rather than competition, support as a response to demand, and a higher social purpose, research becomes more enrooted in local social needs and outcomes. That enrootment, in turn, bolsters motivation and productivity among scholars.

By “enrootment,” we refer to the process, condition, and agency for taking root in the local world, especially as a condition of finding meaning or making an impact. Enrootment lexically means to “cause (a plant or seedling) to grow roots,” to “establish something deeply and firmly,” or to “have as an origin or cause.” It is suggestive of something being embedded, established, entrenched, or having a gravitational pull toward the local.

In the research and writing support community, the mentors and mentoring, collaborators and collaborations were connected laterally; local languages were used where possible; the focus was on process rather than product; and the community was defined by mutual support, purpose, passion, resource-building, and, most importantly, social mission.

Accordingly, our article sought to contribute to the discourse about the academic regime of “publish or perish” spreading across the global south, showing a pathway to what we call a “publish and cherish” framework.

In a world where global south scholars are constantly pulled into the global north, physically and intellectually and where their choices undermine their own local knowledge production (as Adriansen, 2019 unpacks), we argue for the need to go beyond the dynamics of power and hegemony, using support programs to disrupt the global-local hegemonic relationship by fostering scholars’ agency through localization, social impact, and enrootment of their knowledge production. We show how to change the way in which the current map of global knowledge production is itself drawn; for instance, as Czerniewicz (2014) has argued, it is not just the amount and quality/rigor of publications but also how they are measured, whose knowledge counts, who gets access, and who has resources that create and sustain inequality. We must focus on the local purpose of knowledge as the basis of quality and rigor, thereby empowering local scholars to publish in global venues if they wish–essentially rejecting the global-local binary in favor of making scholarship locally purposeful as well as globally useful. We must ask not just who circulates knowledge, or how to improve the citation count of scholars in the global south (a point raised by Mazloumian et. al, 2013) but who produces knowledge and for whom.

We must develop intervention programs to help local scholars publish internationally, as some scholars have done and reported in local and global literature.

Let me now discuss the paradigm shift I proposed in relation to the second half of my argument — that it is when we seek to make knowledge socially and especially locally valuable that we will be able to practically transcend the hegemony of a dominant language, mobilize all our languages, make knowledge and knowledge-making accessible for many more people, and start actually practicing what we preach. That shift requires that we behave and carry out our work very differently — in relation to medium, process, audience, rewards, and recognition.

I propose a new paradigm that I call the “scholarship 2.0” paradigm.

I propose a new paradigm that I call the “scholarship 2.0” paradigm.

The term 2.0 comes from a discourse on the evolution of internet technology. Before around 2003-2006, internet technology used to only allow the vast majority of users to read content published by a small number of people who had special coding and ftp-based web-publishing skills. That was like broadcast technologies such as radio and TV. With the advent of wiki at first, then blogging, then microblogging and other social networking platforms, the internet started allowing general users to write back, to chat with each other, to post and comment in multimodal formats, and eventually to interact in real time.

Imagine that books were not only written by authors because everyone is an instant author, that we’re all on the radio and TV stations, that we’re all journalists and publishers.

It doesn’t mean that we do a good job of any of these, but we are able to. That interactivity, that flattening of the landscape as to who is authority and who is just a consumer, that explosion of opportunity for expression and interaction is what web 2.0 is about. It is a revolution.

Unfortunately, the paradigm shift on the internet — and thereby the mode of communication and collaboration, civic engagement and political power-sharing — has not reshaped academe. The authors are still few, the researchers are both feared and ignored by the public, even within academe the scholars (and not just the lowly teachers and learners) are still up there in the hierarchy. Especially in the global south, and especially in South Asia, our hierarchical socio-epistemic structures and colonial legacies sustain the tradition of Scholarship 1.0 where knowledge is a one-way traffic — and the streets and highways are reserved for the elites only.

This status quo is where the politics of English does its dirty work, and does it quite well.

Practically confronting the hegemony of English(es) requires transcending individual interest and ego, mobilizing all languages in the interest of local society and professions, and engaging in translanguaging and critical global citizenship. Only by producing new knowledge for our own communities and societies—in many languages and new local venues—can we give meaning to our critical perspectives on language.

From the many collaborative projects in South Asia in the past fifteen years, I’ve learned that the politics of global English (including Englishes) can best be countered by focusing instead on our social responsibility and accountability as scholars, by seeking to advance social justice through knowledge production and especially knowledge application, locally. Ultimately, global can and must be the totality of locals–rather than the other way around.

Unequal access to and fluency in English and its elitist forms undergirds significant discrimination in faculty hiring, professional opportunities, and the general attitude toward and respect for scholars–the latest as seen in the case of unequal treatment of faculty who do not have educational degrees from or even low numbers of visits to “native” English speaking countries.

Without shifting from the current paradigm to one that localizes knowledge and pursues social justice, we cannot disentangle ourselves from the hegemony of English(es) and its localized power politics. To borrow the words from the poetry of our colleague Ahmar Mahboob, “Success doesn’t come until your people succeed.” I would add that justice doesn’t happen until we do justice to those around us, rather than just ourselves.

A 1.0 to 2.0 paradigm shift in academe would put the social worth of scholarship at the center by fostering community rather than competition. It would not encourage the me me me scholar on Facebook but scholars who are networked and mutually supporting and producing and applying knowledge for their own community first.

The push for knowledge production away from local venues and audiences is increasingly prompting problematic responses from scholars, such as publications in predatory journals, high frequency of plagiarism and low originality in scholarship, and acceptance of citation index as a goal for new institutional initiatives, if any. In the past decade, the most striking challenges were seen in India, where increased demands for publication (without commensurate infrastructures or support for scholars) led to the annual production of more than a third of the world’s 400,000 articles in 8,000 predatory journals (according to a 2019 Nature article by Bhusan Patwardhan, the former Vice President of Indian University Grants Commission).

In reality, as Mazloumian et al. (2013) have illustrated, citation count may only reflect consumption and dependence on others, instead of setting the agenda locally and putting new knowledge to meaningful use (a point Gerke & Evers, 2006 also raise), as well as contributing it globally.

Especially countries in the global south are now exacerbating that imbalance and the underlying problems instead of addressing them: they are paying little attention to the very purpose of academic publication, while demanding that their scholars meet expectations that are unproductive and often counterproductive, such as to publish in English (which, in fact, is one of the unfortunate reasons for the imbalance), in international venues (another barrier for many), and to meet certain proxy measures of quality (such as citation index, instead of relevance to and impact on society).

To pursue meaningful goals, we need publication venues and peer review processes that are inclusive and supportive, rather than exclusive and judgmental. We must add layers of mentoring to standard review processes, helping writers better communicate ideas across cultures. We need review processes that redefines quality by diversity, rather than prestige and, too often, prestige by the ratio of rejection to acceptance. Quality must also be defined by meaning and value to readers and writers locally. We must also see quality in variety, sharing, and interaction.

Fortunately, we can use the affordances of the web to redefine quality and rigor in ways I just mentioned — but we must our mindsets first.

Now, how do we mobilize other languages, alongside English, to shift the paradigm, to achieve new goals?

First, we must honestly admit that the power of English is based on aspirations and ideologies far more than actual benefits for us and for our society. As scholars have reported from classrooms and communities in global-south contexts like Nepal’s (such as Phyak, 2015; Phyak & Sharma, 2020; Sah & Li, 2020), ideologies about English, as a generic and named language, actually create all kinds of adverse languaging conditions for multilingual users (rather than facilitating resourcefulness and agency).

In an article, also now under review, I report how a group of 80+ Nepalese scholars from across the discipline engage with English in the process of writing for academic publication–especially how they struggle with English and feel ashamed to use their home languages–using the latter in hiding and far more frequently than they think they do. Based on an action research integrated in a 6-month long research and writing support program in 2020-21, the article explores power and politics, ideology and myth-making, coercion and stigma in what I call translingual conditions under duress.

The analysis and theming of data indicated a lower awareness of multilingual practice relative to practice itself, a tendency to overestimate English use in academic research and writing, and a great deal of appreciation for environments that accorded freedom of linguistic choice (in spite of considerable aspirations, among some, to improve English by not using other languages).

I also found that by modeling translingual communication and providing resources in different languages — rather than enforcing any rules or making any demands — the support program had prompted a community of scholars to use different languages as they needed and desired.

But interventions for fostering agentive (rather than inhibited) translanguaging seem to require addressing much broader politics of language and with an understanding of the full languaging condition.

It is for institutions and academic leaders to tackle that larger challenge.

Similarly, how do we take the translingual and decolonial frameworks within the scholarship 2.0 framework?

First, we must pursue collaborative scholarship in and across the global south contexts, contributing to global platforms from the ground up but producing and using new knowledge on the ground first.

Second, we must mobilize the hegemonic impulse for countering that very impulse and to create mutual benefits from which we can advance more meaningful scholarship locally transnationally in the interest of the marginalized communities, not the minority of scholars who pursue their own personal interests in the name of their communities.

And, third, we must translate ethical principles of research into professionally, educationally, and socially beneficial practices; we must start writing in different languages or for different audiences, conducting and publishing research collaboratively, and using scholarship for teaching training and program development.

What stands out for me in the field of language education and communication is the particularly striking irony about how, in a very baffling way, we refuse to speak the different languages in which we ought to be doing our work.

We are as sophisticated as we are self-serving. We are less awkward and more articulate than our less educated neighbors in how we talk–but we are not honest and grounded, not as committed to common good.

আসুন আমাদের সকল ভাষায় প্রকাশ করি। আসুন আমরা আমাদের সম্প্রদায়ের কাছে জ্ঞানকে সহজলভ্য করি।

(Let us publish in all our languages. Let us make knowledge accessible to our communities.)

आइए हम अपने आदर्शों को व्यवहार में लाएं। आइए हम

अंग्रेजी के आधिपत्य की अपनी आलोचना को काम में लाएं।

(Let us put our ideals into practice. Let us put our critique of the hegemony of English to work.)

आउनुहोस, अब छिमेकीहरुको भाषाहरुमा पनि ज्ञान उत्पादन गरौं । आउनुहोस, हाम्रो समुदायकै उत्थान खातीर ज्ञानको प्रयोजन गरौं ।

(Come, let us produce knowledge in the languages of our neighbors. Let us use knowledge for the betterment of our community.)

আমরা কি ধরনের ডাক্তার?

আমরা নিজেদের সম্প্রদায়ের জন্য কি ভাল?

What kinds of doctors are we?

What good are we for our own community?

ধন্যবাদ!