The entry and dramatic increase of “international” or foreign-educated students in the US academy has posed a tremendous and sustained challenge to academic discourse (and thereby policy and practices) because this is a very diverse group. In the absence of (or rather refusal to adopt) better approaches, the US academy has so far tried to tackle the complex challenge of defining the stunningly diverse group known as international students in terms of what they “lack.” The challenge of defining international students is further complicated by the fact that most international students are also “nonnative” English speaking (NNES) individuals, so the issues of the two largely overlapping bodies are conflated together. The result of the two problems above is a fascinating persistence in policy and practice to define international students as learners with “language problems” more than anything else. Continue reading

Category: Transnational Issues

Translation, Multilingual Kids, and Myths about Language Learning

I have read, taught, and talked about teaching and learning language for a long time. But when I think about some of the things that my three and one year old children do with the languages they are learning, it seems to me that some of the most prevalent folk wisdom and even some research/theories about multilingual language learners are inadequate.

Discussions among parents about children’s language learning process in bi- or multi-lingual homes always make me feel that parents have various types of anxiety and concern about their bi- or multilingual children. Continue reading

English Language Proficiency as an Ideological Proxy

In 2009, an Australian nurse gave a 79-year-old patient dishwashing detergent instead of his medication. That crazy person was an international student from India who had just graduated from a nursing school. An investigation, which later caused the nurse to lose his license, showed that he was “unable to read the label” on the container. It is possible that a college-educated person couldn’t “read” the label on a container. And I can believe that professionals who determined that cause were correct. But I cannot help wondering if the whole investigation was driven by an ideologically shaped view of the whole situation.

To explain the above point about ideological framing of the incident–and to consider the implications of that framing for international students across the world–let us look at how the incident was used in an investigative report about the degradation of Australian higher education by an Australian TV. Titled “Degrees of Deception,” the documentary presented the Indian nurse’s case as a perfect example of what is wrong with higher education in the country. Continue reading

One Train from Moocville

The first MOOC–the original concept, that is–originated in an authentic educational experiment in Canada in 2008. That model has been connecting educators, helping them generate a whole host of new ideas around the world.

On the contrary, the things that are known as “MOOCs” by the general public today were created, for the most part, out of a combination of 1) fundamental misunderstanding of the concept of connectivist learning and 2) commercial interest of venture capitalists who find an unlimited supply “star professors” with inflated egos. Replicated in all sorts of, and increasingly, absurd ways, some of these pretend MOOCs continue to alternately fascinate and baffle the heck out of journalists and even scholars of higher education.

But educators who work hard and explore new technologies and adapt them to their contexts and needs in the real world of of teaching and learning have been relatively clear from the outset that mainstream MOOCs can only achieve very limited goals that online pedagogies can achieve when they’re done with an understanding of openness, scale, virtuality, and cross-contextual learning/teaching.

Gaming, More and Less “Advanced”

As I sit down to share some thoughts in the third, gaming-focused week of conversation in the connected learning course, #clmooc, I want to once again start with the friendly Philosoraptor for making my first point. Imagine that you jumped off a spacecraft using a parachute, aiming to return “down” to earth, but then you start wondering if you are falling “toward” or away from or tangentially in relation to the earth. That’s how I often feel about the increasingly hi-tech modes of living and learning.

As I sit down to share some thoughts in the third, gaming-focused week of conversation in the connected learning course, #clmooc, I want to once again start with the friendly Philosoraptor for making my first point. Imagine that you jumped off a spacecraft using a parachute, aiming to return “down” to earth, but then you start wondering if you are falling “toward” or away from or tangentially in relation to the earth. That’s how I often feel about the increasingly hi-tech modes of living and learning.

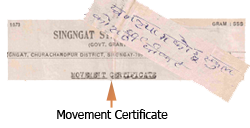

Movement Certificate

“Movement”: A Story of my Life & Education

In the winter of 1987, my father decided to take me along with him on a visit to our home country, Nepal. Due to increasing conflict between the government and extremists in India’s northeastern states at the time, traveling across five states and returning safely to the remote little town in the south of Manipur (close to India’s border with Myanmar) was not easy–not to mention traveling with a ten year old. But daddy had with him good documents from local government offices, one of which was a “movement certificate” for me, written by my school’s principal. After a nifty subject line of “Movement Certificate,” it addressed “whom it may concern” and said: “This is to certify that Master Ghanashyam Sharma s/o Gopi Chandra [Sharma], a resident of Tangpizawl Village, Churachandpur District, Manipur, has been a student of this school since 1980.” It went on to request anyone reading it to kindly let me travel to Darjeeling (in the state of West Bengal in India) and return home to Manipur.

This document, as daddy told me before the trip, would serve at least two purposes: first, it was proof that I was his child–one of the things that a foreigner-looking man might have to prove when inevitably hassled by bad cops, of which there seemed many–and, second, it was a clever way of showing them our home address in India. Daddy had better documents of his residency, but they did the disservice of revealing that he was a foreigner (from Nepal), unlike my document, which only said what part of India we were “residents” of, so this would be a good piece of paper to dig out when questioned where we were from and who we were. Darjeeling, I found out, was the “permanent home address” in the school’s record, a reminder that ethnic outsiders needed an outside address. Never mind that 1) the border between India and Nepal is open by treaty and we shouldn’t have to conceal our identities, 2) those who were paid to be good guys protecting the vulnerable were being bad guys (making money, using hatred of outsiders in the name of law and order, etc), and 3) the effect of good guys acting badly can be very damaging to people’s trust in systems of justice and security.

Continue reading

Invisible Majority of the MOOCosphere–II

In the previous post, I wrote about the unwillingness or inability of proponents of xMOOCs as the future of international higher education. But what I find even more amazing about the current state of affairs about mainstream MOOCs is that the participants from around the world—-including their universities and often their teachers and scholars—-are complicit in the fraud. (MOOCs are actually a blessing in terms of their potentials, especially the affordances they have for truly improving cross-border higher education, but they are a fraud as they are currently pushed by venture capitalists who see nothing but a market and their “star” professors who are too busy delivering their video lectures to the world.

Whether the dominant market-based models will ever be interested in harnessing the real powers of open online learning for cross-contextual higher learning is a huge question at this point.) But from the perspective of the participants around the world, too, the line between honest excitement about their “access” to Harvard and Princeton (i.e., mainly through video lectures and quizzes in all disciplines) and just being stupid is very thin.

Willful Invisibility

I once informally interviewed a college teacher back home in Nepal who had been taking a Coursera MOOC to ask “how effective” he had found the course he was taking. He said that he was “very excited” about the possibility of “going to Harvard”! When I repeated my question about the “effectiveness” of the model of teaching/learning, he emphasized the issue of “access” and of the “prestige” of the providing institution and the teacher. I gave up after a third attempt. This is how hegemony works. Continue reading

Learning as Weapon, Experience, Sense-Making

That title is really weird, right? So was the experience that I’m about to share here at first–although it started making great sense when I got used to the academic culture that I am in now, after some time.

In a graduate seminar and practicum on teaching college-level writing that I took as an MA student in the US, the professor gave the class a literacy/teaching narrative essay assignment. Most of the writing tasks given by professors in various other courses that I had taken until then were all challenging because I was not used to writing “assignments,” but I had been doing fairly well by starting early and working very hard. This assignment caught me off guard! At first, it sounded much easier to write than all the others that I had done, but I was totally stuck because the “idea” behind it made no sense to me and I couldn’t find anything meaningful to say on the subject. Continue reading

Two More Notes About MOOCs–Or Maybe Three

At the end of this summer, after reading a LOT of MOOC news and discussions and writing a lot in emails, blogs, and discussion forums, I almost promised myself to not write a word about MOOC anymore (at least for a year or so). But some of the more recent conversations have helped me learn and think about a few things that may be worth writing. Of course, I don’t mean that there’s nothing good about MOOCs. But the waters in the mainstream discourse about MOOC continue to be so murky that one wants to avoid catching frogs and water snakes when trying to catch pedagogical fish anywhere in the MOOC lake. Continue reading

Naked MOOC Emperors and the Need for Better Conversations about Teaching/Learning Across Cultures

I have taken or at least closely observed a few massive open online courses, or MOOCs, and I want to say out loud that in the case of my own discipline of writing studies, the teachers/scholars running them were wonderful. No, I’m not simply bragging about my own discipline, but like most writing teachers tend to be, the instructors whose courses I took were very thoughtful about students’ learning and in the case of the Ohio State University course, they also seemed highly aware of and sensitive to cultural/contextual differences that can affect students’ participation/success.

However, the more MOOCs I observe, the more it seems to me that no amount of awareness/ sensitiveness is going to be enough. The vastly different academic backgrounds, language proficiencies/differences, sociocultural worldviews, material conditions, digital divides, geopolitical realities. . . make MOOCs fundamentally a paradox. (For convenience, let us call these complex and multilayered differences and barriers just “differences” or “learner differences.”) Here’s why I call MOOCs a paradox: unless the objective of a course is to teach/learn about the differences themselves, trying to accommodate those differences will result in a mess, just because there will be TOO MANY of them in the MOOC setting. For instructors to be able to address enough of the differences, the courses will have to stop being massive, being open, and being asynchronous and online at the same time. That means there is a double bind between teaching effectively and accommodating for the many differences that affect learning. Or is it a hydra? Continue reading